Fossil evidence of 'hibernation-like' state in 250-million-year-old Antarctic animal.

According to new research, this type of adaptation has a long history. In a paper published Aug. 27 in the journal Communications Biology, scientists at the University of Washington and its Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture report evidence of a hibernation-like state in an animal that lived in Antarctica during the Early Triassic, some 250 million years ago.

The fossils are the oldest evidence of a hibernation-like state in a vertebrate animal, and indicates that torpor—a general term for hibernation and similar states in which animals temporarily lower their metabolic rate to get through a tough season—arose in vertebrates even before mammals and dinosaurs evolved.

"Animals that live at or near the poles have always had to cope with the more extreme environments present there," said lead author Megan Whitney, a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University who conducted this study as a UW doctoral student in biology. "These preliminary findings indicate that entering into a hibernation-like state is not a relatively new type of adaptation. It is an ancient one."

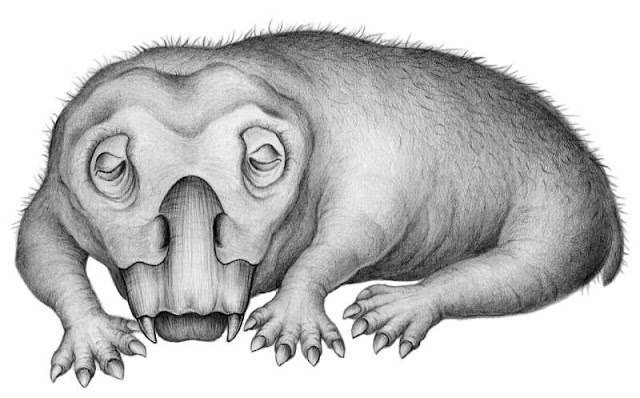

Lystrosaurus lived during a dynamic period of our planet's history, arising just before Earth's largest mass extinction at the end of the Permian Period—which wiped out about 70% of vertebrate species on land—and somehow surviving it. The stout, four-legged foragers lived another 5 million years into the subsequent Triassic Period and spread across swathes of Earth's then-single continent, Pangea, which included what is now Antarctica.

"The fact that Lystrosaurus survived the end-Permian mass extinction and had such a wide range in the early Triassic has made them a very well-studied group of animals for understanding survival and adaptation," said co-author Christian Sidor, a UW professor of biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke Museum.

Comments

Post a Comment